Some links on this page may be affiliate links

An image that no longer impresses

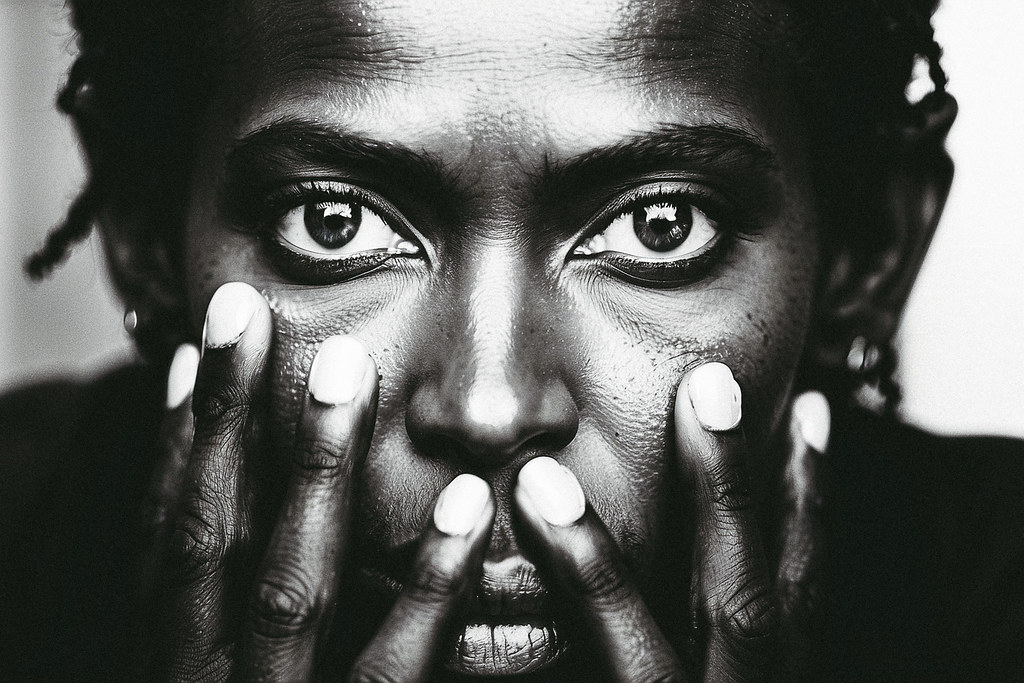

The perfect image has lost its impact. It is sharp, clean, correct — and almost instantly forgotten. In the visual culture of late 2025, a growing fatigue with the aesthetics of perfection is becoming increasingly visible. Images that take no risks. Images without error, and therefore without tension.

There is a growing, often unspoken sense of absence — the absence of human effort, time, and labour embedded in the act of making. An ever-increasing number of generated images adds nothing to the already entropic visual order of the world.

This is not a rebellion against technical quality. It is a refusal of predictability — of endless meta-level repetition. A response to something everyone senses, yet struggles to clearly articulate.

Smoothness as a problem

Images generated and refined to their technical limits begin to resemble one another. The same contrast, similar lighting, identical logic of the “good frame.” They are designed to offer no resistance. To please immediately.

The problem is that this pleasure is fleeting. Perfection functions like a filter — smoothing out everything that might have remained in memory. As a result, the image does not stay with the viewer. It passes through the field of vision and disappears. This is not a single wave, but a continuous process of standardisation — a flattening of meaning that absorbs, levels, and averages visual experience.

A return to imperfection

Increasingly, attention is drawn to images that fail to meet standards. Too dark. Slightly blurred. Accidentally framed. Faces unprepared for the camera. This is not nostalgia for analog photography in itself, but a need for a trace of time and presence. Photography that does not aim to be final, closed, or exhibition-ready. Images that feel like fragments — extracted from the flow of events.

Photography by: Mariusz Nawrocki

This shift is not new. The work of Daido Moriyama has long embraced aesthetic rupture as its defining language. Today, this tendency manifests in renewed interest in analog photography, archival street photography, and in the rising demand — and prices — of iconic analog cameras: medium-format Hasselblads, Leicas, as well as compact legends like the Ricoh GR, Nikon F3, Lomo, or Olympus mju.

Photography as record, not product

In this sense, photography begins once again to function as a record rather than a visual product. It stops proving its value through sharpness or flawless composition. It begins to operate more quietly.

Photography by: Mariusz Nawrocki

This way of thinking about images has long been present in environments shaped by publishers such as Aperture, where photography is treated as a tool of cultural memory rather than a purely aesthetic object. Today, this perspective is returning with renewed relevance.

AI as a catalyst of fatigue

Paradoxically, the development of artificial intelligence has significantly accelerated this fatigue. Images generated by visual models are often “too good” technically, “too perfect” compositionally. They fulfil expectations before those expectations are consciously formed — or perhaps shape them within an overwhelming stream of stimuli.

They may be statistically correct, yet risk-averse. They can be beautiful, intriguing, even surprising — particularly when used consciously as creative tools, something I observe myself when working with AI in selected projects.

Works by: Mariusz Nawrocki

There is no denying that technology can serve as a powerful tool in the hands of a creator, unlocking new possibilities. At the same time, on a broader scale, the so-called democratisation of tools inevitably leads to saturation and devaluation. What could function as art in isolation increasingly becomes just another generated file.

In response, a growing need emerges for images that are not optimal. Images that do not know what they are supposed to look like. Images that have not been calculated, but experienced.

Silence instead of effect

Fatigue with the perfect image does not signal the abandonment of photography. On the contrary — it is an attempt to reclaim it. A return to photographs that require silence. That do not compete for attention, but allow attention to settle.

Photography by: Mariusz Nawrocki

This is also why photography books continue to matter — as a medium free from scrolling and algorithmic pressure. Publications such as classic and contemporary photography books do not strive to be current. They endure.

I hold a particular affection for archival photographic editions. For years, Josef Chladek’s website has offered an invaluable resource — a carefully curated archive of photography books worth exploring.

Instead of a conclusion

The perfect image ages quickly. In a culture of visual excess, imperfection increasingly becomes the primary filter of attention — not an aesthetic one, but a human one. Perhaps the most affecting photographs today are those that do not attempt to prove anything. Too ordinary to become icons. Too ambiguous to become trends. And precisely for that reason, they remain with us longer.

Fatigue with perfection is not the end of the image. It is its correction. A reminder that photography does not need to be better. It only needs to be honest to the moment in which it was made.

Perhaps this is one of the most important shifts of recent years: photography no longer needs to shine. It only needs to breathe.

Further reading

If you are interested in photography free from aesthetic pressure and algorithmic correctness, consider exploring selected publications and albums available on Amazon — for example in the category contemporary photography books. Thank you for reading.